Nadya recently asked “to crowd source a list of resources for creative writers (and their readers!) who are seeking goodness, truth and beauty in their work.” I responded with this comment:

During my own low-residency MFA Jon Fosse and Gerald Murnane were the authors who mattered most to me. I consider them the two best living writers of prose fiction (though Murnane has since retired from writing and is very elderly). I’d place Clarice Lispector in there as well.

Others I found to be excellent teachers include: Adalbert Stifter, Gottfried Keller, J K Huysmans, Robert Walser, Peter Handke, Von Hofmannsthal, W G Sebald, Sibylle Lewitscharoff, H G Adler, Karl Ove Knausgaard, Tarjei Vesaas, Tove Jansson, Sigrid Undset, Jens Peter Jacobsen, Isak Dinesen (Karen Blixen), Rose Macaulay, Rumer Godden, P D James, Bruce Chatwin, Rachel Cusk (Outline trilogy), John Banville, Edna O’Obrien, Elsa Morante, Tolstoy (W&P), Turgenev (Sketches), Leskov, Babel, Der Nister, Mauriac, Henri Bosco, Jean Giono, C-F Ramuz, Pessoa, Melville, Cather, Faulkner, McCarthy, Conrad Richter, Michener, John Williams, McMurtry…

Looming over all the fiction I read then or since, however, is Proust, whom I actually read just before the MFA. In Search of Lost Time is the greatest novel written, and an education in syntax to boot.

Upon reviewing this response, I see that I got some things wrong. In trying to move somewhat geographically through authors, I included some whom, as I admit for Proust, I actually read shortly before the MFA, such as Tolstoy and Ramuz. And upon opening the document which contains my official bibliography for the program, I see several others—Penelope Fitzgerald, Tomas Espedal, Teju Cole, Thomas Bernhard, Zanna Słoniowska among others—who had a powerful impact on me at the time. Some of those I listed, such as Leskov or John Williams, I certainly admired and remember vividly, which explains their recurring to me when I made the comment, but I’m less confident now that I would say they worked for me as teachers.

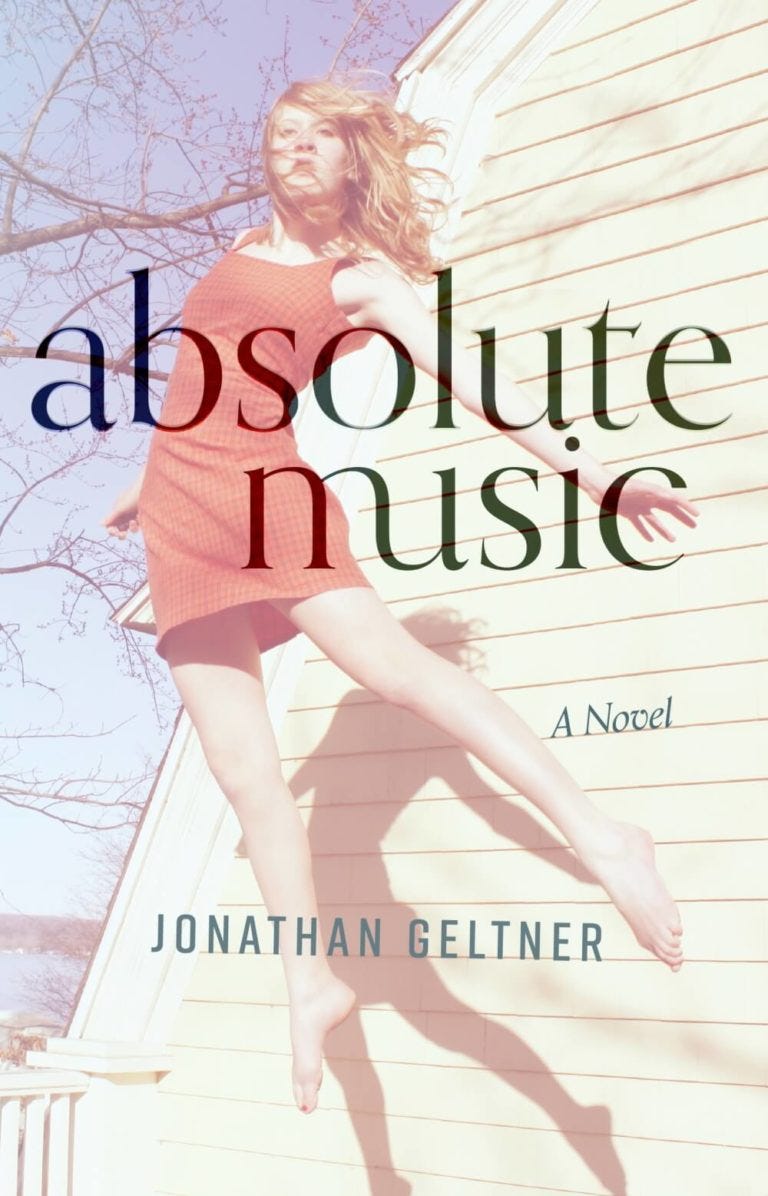

My aim, then, is to revise and expand my initial response to Nadya’s query into something more useful by reflecting on my experience earning an MFA. It was a fruitful time for me: I began during that education to write the novel I wanted to write, later published as Absolute Music. I’m currently finishing up another, very different kind of novel—a combination of romance and metaphysical thriller—which has required a totally unrelated method of research and composition. Though the books I read for my MFA have nothing to do with this project, what I learned by finding out what I wanted and needed to read for Absolute Music has proved invaluable.

As I see it, that is what an MFA ought to give you: not a comprehensive knowledge of some canon—it is not a MA or PhD with their comprehensive exams—but the artistic tools to pursue the craft as your vocation in it leads you to do. These tools include the ability to do a kind of research, but this research does not necessarily put you onto any one kind of writing or historical epoch. Good supervisors will, by looking at the creative work you do during the program, help you discover the directions your research should go.

I should explain something of how my MFA worked and my background coming into it. I attended the low-residency program at Warren Wilson College between 2016 and 2018. I had just turned 34 when I began the program. During that two-year span my wife took up a tenure-track teaching position, moving us from Chicago to southeastern Michigan; we welcomed our first child (no.2 was born three months after I graduated); and I formally converted to Christianity.—Heady times! A year after I graduated, I was working on a translation of Paul Claudel for Angelico Press while I shopped around the novel I had begun in the MFA, and I began teaching at the undergraduate level (where, by the way, little of what I say here is applicable).

I had an unusually literary preparation for the MFA. As an undergraduate I studied English, Classics and French, then spent five years working on a doctorate in English which I left ABD. I read Middle and Old English, ancient Greek, Latin, French, German, and have some proficiency in half a dozen others. It may be the case that someone with less such preparation would benefit from something like a fixed syllabus of canonical authors in their genre, comprising a minority of their total bibliography. The desire to master a tradition is legitimate. In my own case I used some of my bibliography to learn neglected Christian authors (or authors whose Christianity is neglected) like Rumer Godden and Rose Macaulay. However, I hesitate to make even this limited prescription—the strong normative statement about Proust in my initial comment notwithstanding—for an MFA program.

The purpose of an MFA is to get you at least started on a book-length project and to equip you for future endeavors of that scale, and there is nothing in any given “classic” literary work as such that necessarily fits it for that role. Yes, one should read widely if one undertakes to become an author. But one is not obligated as an author to be carrying on any particular tradition. You will discover what you need with the help of supervisors, and along the way you will discover much that is not classical or canonical and which you don’t immediately need. This, I believe, helps keep you the sort of person who still knows how to read for pleasure and healthy curiosity—the chief sort of person, as it happens, for whom you aspire to write.

At Warren Wilson we convened for residencies twice a year, during which time we attended lectures and classes and presented in workshops. We also attended something during residency that we called bookshops: in-depth discussions with our peers, led by a faculty member, of a single book (or, for poets, a single author) chosen by that teacher. Relevance to our creative work was not a stipulation for these bookshops. Those I attended read Yeats, Moby Dick, Shen Fu’s Six Records of a Floating Life, The Rings of Saturn, and Panther in the Basement. The bookshop was one of my favorite aspects of the program, a pure delight separate from any worry over one’s progress as a writer.

Between residencies we corresponded with a supervisor—a different author each semester. The first two semesters were given entirely to reading and writing weekly “annotations” of what we read. In the third semester we wrote the Critical Essay (a thesis of about 50 pages), in my case on the then largely unknown contemporary Australian author Gerald Murnane, the discovery of whose work the previous semester had been a windfall for me. For what it’s worth, I found out about Murnane when my wife brought this article in The New Yorker to my attention. So that’s apparently a venue still worth following.

As an aside, I must confess that I did not during my MFA closely follow any periodical literary publication. And I will admit that I have never found craft essays and books useful. Many of my peers in the MFA read them—often those published by their supervisors—but I never could bring myself to do so and I saw few positive effects of such things in my peers’ writing. We did gain the ability to discuss craft—in workshop, bookshop, writing the Critical Essay, and finally delivering a craft lecture (I find lectures in craft far more useful than books on the subject) in our graduating residency. But I think one is better off getting reading the kinds of books you might like to write and, far more importantly, the kinds of books that make you want to write a book.

Let’s be clear on how much inspiration is called for. Writing (and revising!) a book-length work of imaginative literature is in most cases a long, lonely, painstaking and often tedious process. To succeed in the effort to your own satisfaction—the necessary step before you think of trying to publish—you must be filled with the kind of joy that comes from life itself (and is thus filled with sorrow as well), and from discovering brilliance in the work of others. You want to know what others have found to be possible that is like the potentiality you sense in yourself. Only by finding these authors can you imitate well (from desire), and imitation rather than encyclopedic knowledge of a tradition is what distinguishes the creative from the academic degree.

I’ve far exceeded my remit in responding to Nadya’s initial query, but I feel obliged to address a final point: The desire to publish is also legitimate. I valued the cocoon-like quality of Warren Wilson’s MFA and do not think I would have gotten half out of it that I did, had I been concerned with publication. But I had tried (and failed) to publish two books before entering the program. In the process, I had learned something about publishers and agents and didn’t feel I needed to have that terrain mapped out for me during the MFA. For many people, it might be an important part of the experience (provided it doesn’t make you neurotic), and in that case familiarizing oneself with literary periodicals (especially for poets), query letters and book proposals (for novelists and nonfiction writers) and so on is important.

If you are a prospective MFA student, you should certainly consider what we might call the professionalizing aspect of the programs you’re looking at, and weigh whether publication is of high priority to you or whether you chiefly wish at this stage to be nourished as a writer. It is possible to seek both these ends at once—but not as sanely or thoroughly as one might wish.

You can keep up with Jonathan Geltner’s work by subscribing to his newsletter, Romance and Apocalypse.

A few days ago, I bought a Jean Giono book—Song of the World—found at Dogtown Books in Gloucester, Massachussetts. I'm excited to dig into it.