Your name burns my lips like a Seraph’s kiss,

If I forget you, Jerusalem, who are all gold.

So wrote Naomi Shemer in her iconic Israeli song “Jerusalem of Gold.” Shemer originally composed this for the celebrations in honor of Israel’s nineteenth Day of Independence in May 1967. She selected Shuli Nathan to perform it first, and the recording of her performance with a simple guitar accompaniment still elicits goosebumps.

Shemer’s longing for Jerusalem reflects the reality of May 1967, when Jerusalem was “the city that sits in solitude, and in her heart a wall”—a city split between two countries, although mere weeks away from a reunification. But this longing has deep historical and theological roots for both Jews and Christians.

This song, indeed, echoes Psalm 137, which the weeping exiles from Israel once sang by the rivers of Babylon, asking: How could one ever forget Jerusalem? But, at the same time, how can one praise God while in exile from the promised land? “There on the poplars we hung our harps.”

Shemer recovered her ancestors’ abandoned harps, and made them into violins in her song’s refrain:

“Jerusalem of gold, and of bronze, and of light,

Oh, for all your songs, I am a violin.”

Layered into this love song to Jerusalem are the memories of songs of mourning, like Psalm 137. Singing in Babylon through their tears, the exiles were missing so desperately the place that was God’s promised dwelling with His people before everything went so terribly wrong.

These distant memories, at the same time, are inseparable from the memories of much more recent loss and suffering—at the time of Shemer’s composition, the Holocaust was just over twenty years removed, and the country of Israel still a teenager. This made Jerusalem, along with the rest of Israel, a place of loss, filled with people who had known much sorrow, but who in their own suffering drove out and inflicted much violence upon another people, who too knew much suffering and loss both before and since. The recent events in Israel—the war ongoing since October 7, 2023; the hostages still away from home even now; the many civilians killed in Israel and in Gaza—only highlight this further.

There is no question that the history of Jerusalem is heavy.

But Shemer’s song also echoes the longings of pilgrims who traveled to Jerusalem so long ago, who first composed Psalms of Ascent, to be sung while approaching this holy place in order to get one’s mind and heart in the right place. And two millennia ago, one among many who made this very ascent and surely sang these very Psalms, first with his parents and later in adulthood, with his disciples, was the incarnate God himself.

Those exiles who first sang Psalm 137 in Babylon, weeping bitter tears over their longing for Jerusalem, had no idea that their dream of redemption would come true in such a spectacular way a little over half-millennium later. But then, neither could any of those who once made the ascent with Jesus at any time during his lifetime, have imagined who was in their midst. What a strange redemption the events of the week leading up to the crucifixion would have seemed to any of these exiles or pilgrims. And how strange these events seemed to those eyewitnesses who could not grasp the astonishing conclusion to the week.

Despite the prophecies that in retrospect may seem so clear, no human truly imagined that the same God who parted the Red Sea to take his people out of Egypt earlier in their history—the miracle that the Jewish Passover still commemorates!—would also willingly choose to be arrested on Thursday and executed in the most gruesome way imaginable on the Friday of the week of Passover. But the tomb will be empty on Sunday.

I am a citizen of Israel and the United States. I grew up in a secular Jewish household in Russia and Israel and came to Christ as an adult. As I wrote two years ago in trying to explain my conversion, the Holocaust and Russia’s horror-filled history are part of my family’s story. For my mother, in particular, this reality means that for me to choose Christ was the ultimate betrayal of my Jewish roots.

Theologically, she is correct. To choose Christ does indeed mean to let go of everything else. This does mean a betrayal or (to use a nicer word) renunciation of every other identity. But more than any other time of the year, during the week leading up to Easter, it seems particularly clear that my choosing Christ is not a betrayal of my family’s heritage. It is, rather, its fulfillment.

Judaism and Christianity are historically rooted. In the eyes of believers, key events underlying their faith really did happen.

Sometimes, as we think about theology and beliefs in the abstract, it is easy to forget this key truth. But Holy Week centers on the historical events that took place in Jerusalem almost 2,000 years ago. This is, therefore, a time that particularly demands us to notice and feel within our very being the blending of the historical past and the present, the visible and the invisible, sorrows of the past and suffering yet to come, but most of all, promises fulfilled and profound joys that so far have only been foretold, and which we cannot fully imagine.

The events of the cross and the Resurrection foreshadow more cosmic events to come that will revolve around Jerusalem, but it will not be the city we know here on earth.

We have returned to the water cisterns, to the marketplace, and to the square,

A shofar calls on the Temple Mount in the Old City.

And in the caves within the mountain, a thousand suns shine bright,

And again we will go down to the Dead Sea through Jericho.

Jerusalem of gold, and of bronze, and of light,

Oh, for all your songs, I am a violin.

Our souls long for a Jerusalem that is not here; has never been here. The Resurrection promises that one day, we will see it.

This reflection originally ran at The Arena blog at Current.

Three Essays Elsewhere This Week

Last fall at church, I appreciated the opportunity to co-teach a women’s Sunday School class on Ecclesiastes. So naturally, I was eager to read pastor and theologian Bobby Jamieson’s new book about Ecclesiastes—Everything is Never Enough. I thoroughly enjoyed it, and here’s my review, from the Spring issue of Common Good Magazine.

A taste from my review:

Just picture, hypothetically, a guy who has it all — the best job with all the best perks, exorbitant wealth, romantic success, children, the best food and drink, the best house. That is the description of the privileges that are the purview of Qohelet — also known as the Teacher or the Preacher — who presents his reflections in the philosophical book of Ecclesiastes. He has tasted and experienced all of the best things in life, and all he learns is that it’s never enough. It’s all absurd — or meaningless or vanity, depending on your translation. Why? Because that is life since the fall. That is the underlying assumption of Qohelet’s frustrations, Jamieson explains. Whenever we strive in vain — and especially when we recognize that this is what we are doing, whether at work or in other areas of life — the reason, Jamieson writes, is that “Humanity as we encounter it now does not reflect the factory settings. … We were not always selfish at others’ expense.”

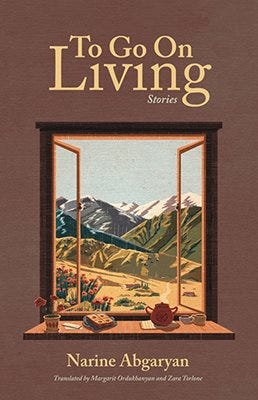

For Religion & Liberty Online, I reviewed Armenian writer Narine Abgaryan’s new short story collection, To Go On Living. The stories are heavy, they tell of war and death and destruction in a part of the world that has seen so much tragedy that doesn’t make it into our news. Yet these stories also show the power of the cross in giving people the necessary hope to go on living after tragedy.

So much of modern life after the Industrial Revolution is about scaling everything up. Except, that’s not how people work (those “factory settings” Bobby Jamieson writes about in his Ecclesiastes book). For Institute for Family Studies, I wrote about the joy of inefficiency projects—especially, the joy of teaching kids to read. I realized recently, with shock, that I

wastespend ca. 1,000 hours per year reading to/with my kids. One of my takeaways:We must recognize an important truth: inefficiency is the key to good parenting. Children require a significant time investment from their parents to thrive and grow. But then, relationships with adults require no less significant time investment. Without it, all our relationships—whether with friends or family-members—only atrophy over time. Perhaps, in other words, we need to embrace that all our relationships with other people are two things that we generally consider contradictory: first, they are absolutely essential for human flourishing; and they are inefficiency projects.

Once again, well done, Nadya.

This is a beautifully written column. All of us sinners must stay loyal to Christ. Romans 10:9 states “ because if you confess with your mouth that Jesus is Lord, and believe in your heart that God raised him from the dead, you will be saved.” Reading what Nadya Williams writes speaks to my mind and soul.