A year ago, I found the above message on my kitchen fridge. It seems an apt summary of one aspect of parenting. But also, like all utterances, such threats take on a different flavor depending on the context. Seeing this on our fridge, my husband and I laughed, snapped a shot for the memories, and went on with our day. But what if you are a small state and you get such a demand from another state, bigger than you, and capable of inflicting real damage if demands aren’t met?

This week, we’re continuing with our discussion of Thucydides, covering Book 1, sections 24-88 (pages 16-49 in this edition, if you’re using it). And the overall tale of threats and diplomacy fails we are covering this week could, in effect, be summarized in the whiteboard message above.

But first, a little bit of background.

Greek Colonization

An essential chapter in the history of the Greek city-states in 7th-6th centuries BC is colonization, which Thucydides had mentioned in brief in last week’s reading. Now we see why it’s important. In a nutshell, whenever a “mother” city established a colony, it sent out a new city-state that owed some degree of obligation to the mother state. The entire point of a city-state establishing a colony was profit—and many colonies were established for the purposes of trade. A colony on an important trade route, or with a good harbor for shipping goods, was an asset.

The diplomacy fail that we’re reading about this week has to do with the relationship of three prosperous city states: Epidamnus, founded as a colony of Corcyra, which itself had been founded as a colony of Corinth. Here’s what Thucydides tells us:

The city of Epidamnus stands on the right of the entrance of the Ionic gulf. Its vicinity is inhabited by the Taulantians, an Illyrian people. The place is a colony from Corcyra, founded by Phalius son of Eratocleides, of the family of the Heraclids, who had according to ancient usage been summoned for the purpose from Corinth, the mother country.

Heraclids, by the way, means “children of Heracles”—meaning, descendants of the mythical hero. When designating official founders for a city, you want folks with the best ancestry!

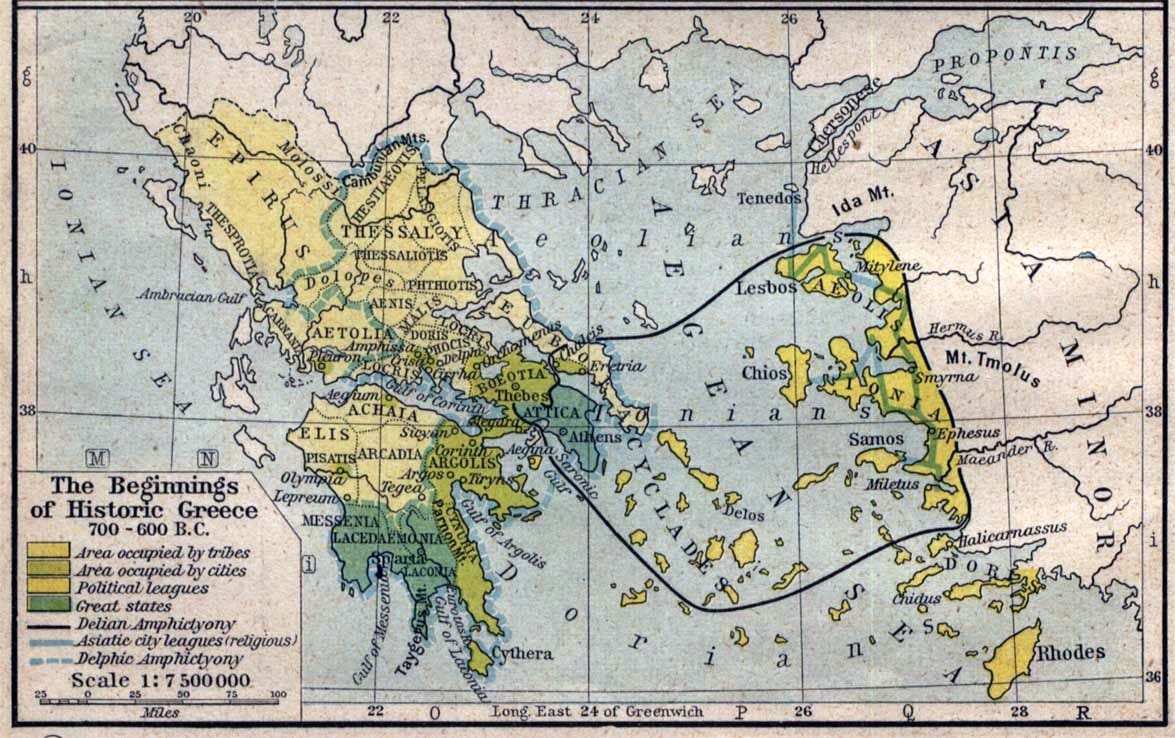

The geography matters here. Corinth is located right under the 38th parallel in the lime green on this map. It’s close to Attica, where Athens is located. Corcyra and Epidamnus, not marked on this map, are both bordering the Ionian Sea and are far to the north of Corinth, on the left-hand side of this map, just under the 40th parallel.

Trouble Begins—and a Delphic Interlude

It all started with civil strife in the city of Epidamnus. The People (the Demos) expelled the oligarchic party from the city, but the exiled oligarchs joined forces with “the barbarians” (aka non-Greek residents nearby) “and proceeded to plunder those in the city by sea and land.” The people of Epidamnus asked Corcyra, their mother city, for help, but Corcyra refused.

Next, the people of Epidamnus did what all thoughtful Greeks at the time would have done: they sent a delegation to the oracle at Delphi to ask whether they should ask Corinth, their grandmother city, for help.

A brief word about the Delphic oracle, named the Pythia.

There were several oracles in the Greek world, but the most famous one, respected by all Greeks, was the oracle of Apollo in Delphi. Sitting in a cave with mysterious prophecy-inducing fumes, the Pythia would go into a trance and give a prophetic response to questions asked of her in perfect hexameter poetry. Of course, the problem was always how to interpret her prophecies, which could be rather obscure.

The earlier fifth-century historian Herodotus tells us how the Lydian king Croesus once asked the Pythia whether he should go to war against Cyrus. She told him that if he went to war, he would destroy a mighty empire. Croesus thought this meant his victory. He was wrong. Awkward.

But in the case of the Epidamnian delegation, they got a clear answer, at least as far as Thucydides tells us: yes, go ask Corinth for help. So they did. Maybe they should have thought back to Croesus’s experience though.

New Alliances—and Old

Corinth got a fleet read to come help Epidamnus, but suddenly, Corcyra got worried and sent a delegation to Corinth to try and avoid war. But neither side was willing to back down, and the Corinthian navy faced Corcyra in battle, with an unexpected outcome: Corinth lost, then Epidamnus surrendered. So much for the oracle’s advice. Suddenly, at least for this moment, Corcyra took full control of Ionian Gulf.

Corinth, however, spends the next year preparing to return and retaliate against the Corcyraeans. So Corcyra turns to Athens to get help, and both Corcyra and Corinth send delegations for a diplomatic discussion. Thucydides quotes multiple speeches in this section—and perhaps some of them, at least, are based on witness accounts. In particular, he notes these arguments from Corcyra to Athens:

yourselves excepted, we are the greatest naval power in Hellas… If it be urged that your reception of us will be a breach of the treaty existing between you and Sparta, the answer is that we are a neutral stat, and that one of the express provisions of that treaty is that it shall be open to any Hellenic state that is neutral to join whichever side it pleases.

Corinthians are not convinced and make it clear that if Athens comes to the side of Corcyra, they will take it as a violation of the previous treaty they have with Athens.

A battle soon occurs, in which the Corinthians almost rout the Corcyraeans, but Athens (who mostly watched the battle from the sidelines) prevents a total victory. If you thought Corinth couldn’t get more upset with Athens at this point, think again.

The Revolt of Potidaea and the Conference at Sparta

Immediately after, one more source of conflict arises for Corinth and Athens, over the city of Potidaea, which happened to be a colony of Corinth, but a tribute-paying ally of Athens.

And so, the final round of diplomatic talks in this week’s reading takes place in Sparta. Here’s what the Corinthians have to say about the Athenians:

To describe their character in a word, one might truly say that they were born into the world to take no rest themselves and to give none to others.”

Ouch. The Athenians, in reply, note their distinguished record fighting for the Greeks in the Persian Wars, and of course, their work on the prosperity of all. Finally, Archidamus, the wise old king of Sparta, urges his people to pursue peace.

In ancient literature, the final argument made in a series of speeches in a debate is always the one that wins. And the final argument here is by a Spartan ephor (a high-ranking official), Sthenelaidas, who does something unusual here: Normally, Spartans voted in assembly by shouting, and the loudest position won. In this case, he urges Spartans to vote for war—and asks them to separate into two sides of the assembly space, voting with their feet. It worked.

Thucydides’s analysis of this result is one of the most poignant moments in his history:

The Spartans voted that the treaty had been broken, and that war must be declared, not so much because they were persuaded by the arguments of the allies, as because they feared the growth of the power of the Athenians, seeing most of Hellas already subject to them.

Fear. This war was a diplomacy fail that escalated from a small regional dispute, once larger powers got involved. But Sparta’s involvement, which finally pushes the war forward, is the result of fear. It was in Sparta’s power to de-escalate this. But it didn’t.

Next week’s reading assignment: Book 1, sections 89-146 (pages 49-85 in this edition, if you’re using it). This will take us to the end of Book 1!

Two More Things Elsewhere This Week

The Reading Wheel Review, published by the Center for Religion, Culture & Democracy at Baylor University, invited me to write an essay on Stephen O. Presley’s encouraging new book, Biblical Theology in the Life of the Early Church. So I wrote about “The Bible Readers Who Loved Their Book.” A taste from my conclusion:

Presley extends a call that is simple: as Christians, we are direct spiritual descendants of the earliest believers. And so, it makes sense for us to learn to think about the Bible through their eyes, to the extent that we can. The fruit of faith that their love for Scripture brought in their lives and in the explosive growth of the early church speaks volumes.

But there is an additional implication of Presley’s study, which I endeavored to bring to the fore in my two examples of early Christian readers who were not engaged in pastoral roles. The vast majority of Christians in every period of the history of the church are called to be sheep rather than pastors. But the call to know the Bible deeply—to absorb its beauty and its call to faith into every fiber of our being—applies to shepherds and their flock alike. And, as Presley puts it, “To discern the spiritual sense, the Christian exegete should adopt a way of reading that explains how the Scriptures point to Christ.” It goes without saying that every pastor should be such an exegete, but it is appropriate to remember that every Christian in the pews should heed this call too.

I enjoyed reading and reviewing James Rebanks’s gorgeous new book, The Place of Tides, for Mere Orthodoxy. A taste:

In his new book, The Place of Tides, farmer, journalist, and award-winning author James Rebanks documents a recent spring he spent shadowing one "duck woman," Anna, during her final season stewarding eider ducks on a tiny island, Fjærøy. Its name, translated into English, means “the Place of Tides,” after the tides that sometimes allow the island and the tiny rocks around it to be a single landmass whole, and at other times make them seem as a grouping of unrelated rocks, separated by deep waters. In the process, the quest that began with curiosity turned into love—for this island, for the eider ducks, for Anna and those like her, living stubbornly in a world that no longer exists. The latter category includes, of course, the author himself.

This section of Thucydides treatment of Athens reminds me of a partial quote by Chesterton “My country, right or wrong is a thing that no patriot would think of saying…” It appears that Athens at this time was governed by a version of might makes right. We as Christians should be governed by Christian thought that would assist us in determining what is right in a sinful world.

The Trump approach to international relations appears to be how a Mafia don might approach

the world.